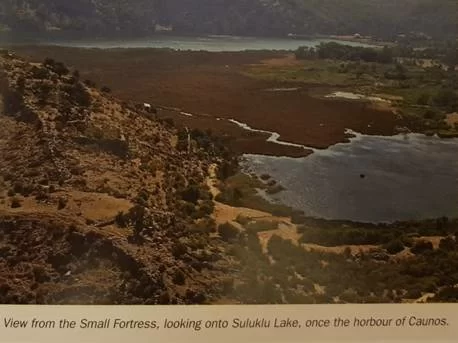

Yes, the delta created by reed islets is chaotic, but this incredible land that is in constant flux, reshaped by the divine order, inspires feelings of awe and joy. There are four lakes worthy of exploration, the first of these Sülüklü lake, was once the port of ancient Caunos, and the life blood of its economy. This busy harbour was frequented by the tilted-nosed, square-sailed ships of antiquity and was according to Strabo ‘protected with a chain across its entrance when necessary’. Today, it is altogether cut-off from the sea with the alluvial deposits and clumps of reed that have covered its entry. The shortest way to get to it is to leave from the wooden pier next to the fish barriers, passing by the archaic walls and proceeding to the agora of the ancient city.

The rocky crag that covers of the east of this former bay was the religious centre of Caunos, situated on its small Acropolis with the Temple of Demeter. There were probably shipyards at the shore of the tree-covered cliff in the east facing the bay (See: Caunos Guide). Standing at the shore of the Sülüklü Lake and watching the reflections of the past shimmering on the surface, your imagination takes you back to antiquity. The wind might even carry to your ear the sounds of the crew trying to load or unload their goods, the trades suspicious customs officers. The “customs regulations” on the face of the fountain overlooking the port, tells the story of Caunos founding and its vital economic connection to the sea and then details its decline as a direct result of the silting up of its harbour.

The second lake is Alagöl, which is situated to the east of the delta and at a location close to the sea. In the Alagöl Lake, accessible through a wide channel that skirts Kızıltepe, (a hill where the pine trees cling onto the rocks to reach the water), there is Çandır Village pier hidden deep among the greenery at the edge of the mountain. Çandir, which is probably older than Dalyan and which might have been founded by the first Yoruk (nomad) tribes inhabiting the area in the 13th century, is just beside the ancient city of Caunos.

The therapeutic mud extracted from the bottom of the lake, (warm even in the winter due to the thermal spring on its bed), provides the skin with a youthful lustre, thanks to the high content of minerals and its organic structure caused by decomposed reeds.

Close to the wooden pier where the inhabitants of Çandır moor their boats, on the surface of the cliff by which the Kiziltepe hill meets the water like a wall, there are about 50 rectangular holes like the windows of a high building looking out beyond time. These are niche tombs, the likes of which can be found in Caunos’ northern necropolis. Cremated bodies placed in urns were deposited into the small cavities within the floors of the niche. After the funeral ceremony, the mouth of the niche was covered with a plaster-fixed stone these funerary items are recorded but the physical evidence doesn’t exist.

This mysterious lake, where the sorrow of death shivers on the lake’s surface, brings many archaeological questions to mind. Was the Alagöl Lake used as a port for some time a longer had connection with the sea? Perhaps Caunos’ shipyard mentioned in ancient sources it scans an exact location, was installed at the side of Alagöl providing a suitable place for ship building and repairs given the wide land behind it? Or were the seamen and fishermen who inhabited this area buried there to be close to the sea for which they had a passion, even when dead, to view its vast blue as spirit mariners?

The third lake is Sulungur, an old lagoon situated at the east end of the delta. Surrounded at three sides by the forest-covered rocky promontories, the Gökbel Mountain, the lake is fed by the gullies that carry the rainwater in winter as well as by the fresh water of the springs flowing from the surrounding rocks. You can access Sulungur’s undefiled, consummate beauty by exiting the to of Dalyan, going around the lake by the road that stretches towards Iztuzu. Or you can travel by boat passing through the gate of the “small fish trap” installed at the location where it connects to the large channel between the Delta, lake and Iztuzu Beach.

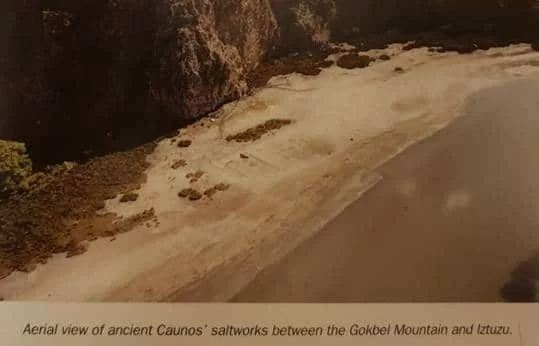

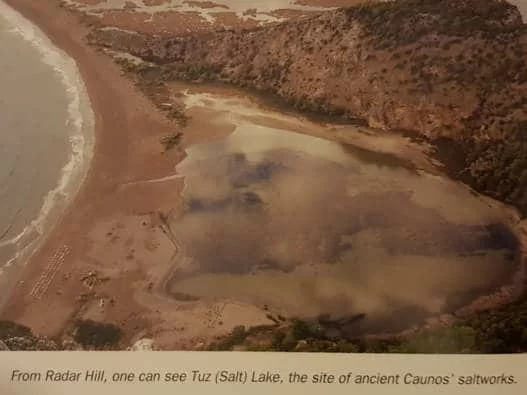

The fourth lake is between the promontory of the Gökbel Mountain (that goes down to the Dalyan delta like a tongue) and the Iztuzu Beach is a saltwater lake that is no deeper than one metre. This is a small shore lagoon that fills when the sea rises and the waves pass the sand strip in winter and dries and turns into a swamp in the heat of summer, houses an ancient salt works that is very important in Caunos’ history.

Economic difficulties were experienced when the entrance to the Caunos port started to silt up with reeds and mud. The “customs regulations” on the port side of the Agora Fountain, thought to have been inscribed during the first years of the Roman Emperor Hadrian’s reign (117-138 BC], mentions tax and donation exemptions provided to increase maritime trade, but expresses that the tax imposed on salt and slave sales shall remain as before. In his famous work “Naturalis Historia”, Roman historian and natural philosopher Pliny indicates the importance given to salt from Caunos in antiquity when he writes “salt is a therapeutic substance for the eyes and therefore is mixed in pomades for the eyes. For this purpose, usually Tatta (the Konya Salt Lake) and Caunos salt is preferred.” Like it is today, fishing was a vital he region in those day for its use in preservation; drying, smoking and salting large amount of caught fish.

“Where did the inhabitants of Caunos install their saltworks?” This important question was answered only in 2007. As is the case with many archaeological questions, the answer was somewhere very close, even in sight. In any case, the name “Iztuzu (trail salt) Lake” was already a sufficiently clear answer. The excavation team directed by the inhabitants of Dalyan found the Caunos salt on the shore visible under a thin layer of sand. The salt works, which was installed on a rectangular plot of sand and projected out towards the shore, was divided into three full and two half parcels. Three canals and salt pans were constructed facing each other at the two sides of the canal. Both the flat pans, which have an average diameter of 1,60 m and a depth of 0,40 m, and the canals to which they are connected were lined with lime, covered with gravel and plastered (Işık-2008).

TIP: On our Noon to Moon and Sunset Supper tours you will have the opportunity to swim in the warm waters of Ala Göl

Pliny also gave us important information on the salt works operations in antiquity. “Sea salt is obtained either when the sea has receded or when the seawater collected in pans along the shore evaporates.” The fact that the Caunos salt works was found intact is very important with respect to world archaeology. The salt works was installed in a location that provided the ideal conditions to accelerate the process; it is located right in front of the protrusion where the rocks form an inlet into the beach. When the seawater poured into the pans through the salt works’ canals, evaporates due to the heat coming from the rocks that are in turn heated by the summer sun as well as wind turbulences, the valuable sediment of white salt crystals remain in the pan.

Source: Koycegiz – Dalyan A Journey Through History Within The Labyrinth of Nature, (pages: 54-59), Altan Türe, 2011, Faya Kültürel Yayınları

Comments