Natural beach with fine golden sand, draws the boundary between the Dalyan Delta and the sea. The length of this sand spit that starts from the skirts of the Radar Hill and ends at the point where the Dalyan River flows into the sea or the “Dalyan Mouth” in the local expression varies between 5 to 6 kilometres depending on the shifts in wind and the waves that shape the dunes.

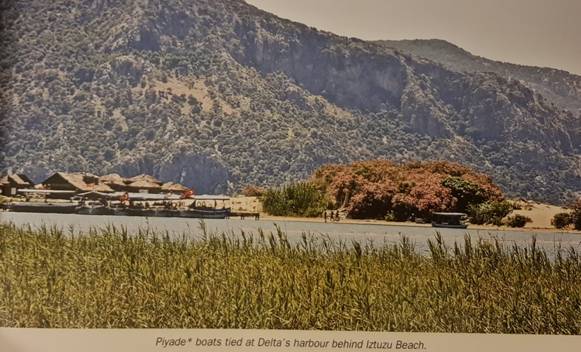

Iztuzu and the Dalyan Gate is the magnificent final of the Köycegiz – Dalyan ecosystem and the place where the Dalyan River meets the Mediterranean. The threshold of this strait is the Delik Island that rises opposite to the Dalyan Gate and is covered with pine trees and scrub. Having a pier and a lighthouse at the side facing the Iztuzu beach, the Delik Island was a point of bearing showing sailors of the antiquity the entrance to the port of Caunos. After the bay was covered with swamps and dunes, it started to be used as a loading berth for transporting cargo and passengers from the Delta to the sea and vice versa.

Iztuzu and the Dalyan Gate is the magnificent final of the Köycegiz – Dalyan ecosystem and the place where the Dalyan River meets the Mediterranean. The threshold of this strait is the Delik Island that rises opposite to the Dalyan Gate and is covered with pine trees and scrub. Having a pier and a lighthouse at the side facing the Iztuzu beach, the Delik Island was a point of bearing showing sailors of the antiquity the entrance to the port of Caunos. After the bay was covered with swamps and dunes, it started to be used as a loading berth for transporting cargo and passengers from the Delta to the sea and vice versa.

The world’s second beach which preserves its naturalness, the Iztuzu beach is a natural wonder. On one side it has the delta’s still, green and fresh water while on the other stretches the crystal-clear blue water of the Mediterranean. In the lace-like beauty created by the white foam of the waves that break on the shallow and sandy bed of the sca before hitting the shore and the roar of the almost continuous wind that merges with the sound of the waves, there is the lyrical call of the virgin nature that frees one.

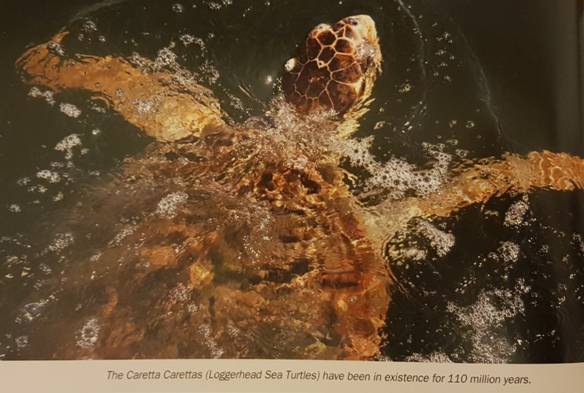

Sea Turtles Nestling at Iztuzu Beach

The Iztuzu Beach that lies as if never touched before actually hosts a very busy life. Iztuzu is one of the most important mating and egg-laying grounds of the sea turtles of the Caretta Caretta species on the Mediterranean. However, as the hot period between April and September, their mating season, coincides with the tourism season, the beach gets rather crowded. The continuation of the Caretta Caretta species, which was designated as an endangered species by International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources (IUCN), is very important for all humanity so that the natural chain of life remains intact. The measures taken by the Special Environmental Protection Agency (TR: Özel Çevre Koruma) are successfully implemented thanks to the efforts of academic institutions and environmental protection volunteers and the support of the inhabitants of Dalyan.

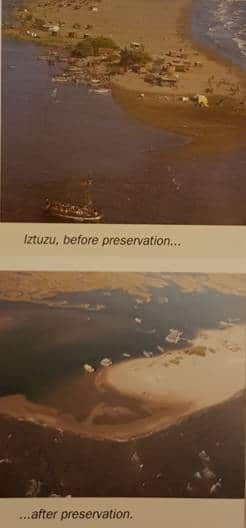

Today Iztuzu is free of all the sheds that were built on it and has been cleaned and rearranged with a controlled and sparse building policy. Tourists coming to throw themselves into the warm blue water of the Mediterranean are able to use the beach only during the day, and they are forbidden to bring pets, as this may harm the eggs which the Caretta Carettas lay into holes they dig in the sand.

After dark Iztuzu Beach is empty, with the exception of a few night-watchmen to ensure that any man or man-made lighting be removed. This is to prevent the young sea turtles from becoming disoriented as they instinctively make their way from their hollowed nests in the coolness of night, using only the reflection of the moon and stars to guide them to the sea. With this protection nature’s balance is restored as the beach is left to the sea turtles, sand crabs and other animals of this habitat to do what nature had intended them to do at night.

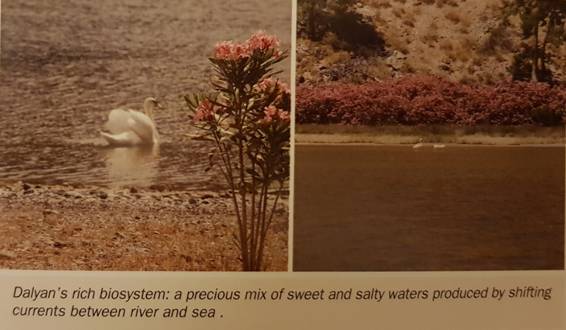

The strait through which the Dalyan River brings the Köycegiz Lake’s waters into the sea, (known locally as the “Dalyan Mouth”) is a natural valve of the ecosystem, which regulates the sweet and saltwater currents and the wealth of life created by their mixture. Depending on the increase in the lake’s water level due to the slight tidal movement of the Mediterranean, the waves caused by strong winds or rains, sometimes freshwater flows into the sea while sometimes seawater enters the Delta. Where shallow sea and the Delta meet, shifting sand beds continuously alter the depth of the strait depending on the direction and rate of the currents. It is not possible for large boats and deep yachts to enter the ecosystem through this capricious pass. Indeed the “piyade” boats specific to the region were designed so as to be able to reach the sea through this strait, a design that has probably been in use for centuries.

Iztuzu Beach in History

With the data we have, it is possible for us to imagine any the question “What happened in Iztuzu?” when the delta formation was completed and it was closed in by a strip of sand in the centuries following the Christian Era. Historıcally, here was no doubt a seasonal settlement, home to storehouses and piers used by the fishermen and seamen, located right next to the Caunos salt works which would be very busy during the summer. Mention of a customs checkpoint in order to check the salt and fish trade in an inscription found in Iztuzu appears to corroborate this view. However, as the archaeological research on the vicinity surround the saltworks is not completed yet, it is not possible to say anything certain about the size and the buildings of this settlement.

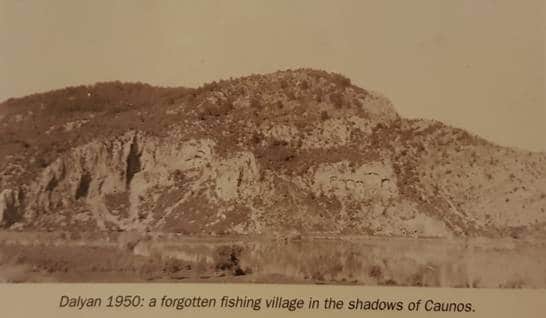

During the Menteşeogullari Emirates and Ottoman Empire periods, the town of Dalyan was an important seaport from which the agriculture and forestry produce of the towns of Dalyan and Köyceğiz as well as the vicinity would be shipped to Rhodes and to other Aegean islands through the Dalyan River. In order to regulate this import and export traffic a customs office was established in Dalyan, probably after the 14th – 15th centuries. The customs officers worked at the Dalyan Mouth, that is the Iztuzu beach, where it was easiest to keep the entries and exits to the waterway under control.

However, historical sources are inadequate for the period preceding the mid-19th century. The memoirs compilation made by Şevki Alican, who is a local of Dalyan, provides important information on the recent history of the town, on the customs house and on the Iztuzu beach for the last 150 years (Karaağaç-2009).

The reputation gained by Kamil Keskin, the grandfather of one of Dalyan’s most famous shipbuilders with the same name, for building and operating large boats has reached today. Kamil Keskin, the elder emigrated from Yugoslavia to first Rhodes and then to Marmaris, building boats there, then settled in Dalyan to work as a “reis”, a controller of the strait, at the Dalyan river strait. He built and launched five boats and four barges of sizes between 14-26 metres in the shipyard he established at the Dalyan Gate.

The barges with the flat bottoms used to be used in times when the entrance of the strait became shallow due to sand accumulation. Cargo such as agricultural products, honey and forestry products carried by boats coming from Köycegiz and Dalyan would be loaded onto ships sailing from Rhodes and anchored before Delikada, and the cargo of the ships such as sugar, tea and drapery would bepassed through the strait in the same way and transferred to the small boats. In his memoirs Kamil Keskin mentions that his grandfather had a “charity house” built at the strait to accommodate the sailors of the ships that travelled between Rhodes and Delikada during loading and unloading operations. Relying on this account we may assume that by the end of the 18th century there was a building complex comprised of a shipyard, guests lodgings as well as a pier close to the Dalyan Gate on the Iztuzu Beach. In addition to these, a gendarmerie station was built 100 metres to the south of the strait side of the beach in 1930 for the security of the area, but was closed towards the 1950’s.

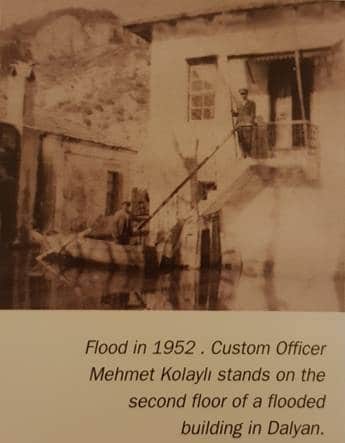

The development in land and air transportation after the 1960s rendered small piers and sea transport with small-tonnage vessels. Like many others on the Aegean and Mediterranean shores, the Dalyan pier ceased to be important. A black and white photograph of the last period of the Dalyan customs office is an important document since it also shows the people using boats in the streets due to the flooding in Dalyan caused by heavy rain in 1952. The uniformed person seen in the photograph, standing on the second floor of the small customs office built of stone in the lower floor and mud in the second, is Mehmet Kolaylı (Customs Officer Mchmet) who was appointed as customs officer to Dalyan in 1951.

The development in land and air transportation after the 1960s rendered small piers and sea transport with small-tonnage vessels. Like many others on the Aegean and Mediterranean shores, the Dalyan pier ceased to be important. A black and white photograph of the last period of the Dalyan customs office is an important document since it also shows the people using boats in the streets due to the flooding in Dalyan caused by heavy rain in 1952. The uniformed person seen in the photograph, standing on the second floor of the small customs office built of stone in the lower floor and mud in the second, is Mehmet Kolaylı (Customs Officer Mchmet) who was appointed as customs officer to Dalyan in 1951.

Over time sands carried by the winds covered the shipyard and other buildings on Iztuzu. The sea and sun holiday trend in domestic and foreigntourism in the 1970s also affected the inhabitants of Dalyan. In his memoirs, Şefik Alican mentions that some families, in order to get away from Dalyan’s mosquitoes and heat, built small shacks and started to live on the Iztuzu Beach in the summers. Only a mulberry tree and a water pump to the left of the old gendarmerie station, between the Gebekum and “Küçük Dalyan” locations remain as a memory of this seasonal settlement on the delta side of the beach (Karaagaç-2009). Also eliminated were three shack-restaurants, two of which were built on the strait side while the other was built on the point where the road from Dalyan connects to Iztuzu, received their guests, offering them fresh fish and plenty of salad. Comfort was not one of Iztuzu beach’s best features in those days; but sitting around a fire at night, singing together, and making conversation that would go on until daybreak were unforgettable pleasures.

Then came an upsetting truth; the baby Caretta Carettas, coming out of their eggs at night instinctively heading towards the sea and moon guided by the moon light and stars, were becoming disoriented from the campfires and bright lights of the beach residents. When unable to find their way, they died from dehydration or attacks by seagulls.

Then came an upsetting truth; the baby Caretta Carettas, coming out of their eggs at night instinctively heading towards the sea and moon guided by the moon light and stars, were becoming disoriented from the campfires and bright lights of the beach residents. When unable to find their way, they died from dehydration or attacks by seagulls.

Upon a protective mandate for new generations of Caretta Carettas (considered as one of the oldest living species of the world, but facing extinction) all shacks were demolished. After the entire ecosystem was proclaimed a “Natural Reserve” in 1988, the beach was rearranged under a very limited and careful building plan that would not harm the eggs and young turtles.

When a British traveller by the name of June Haimoff (affectionately referred to as Captain June) moved to Dalyan, she attracted global attention to the sea turtles plight as well as Iztuzu beach conditions. Preservationists world-wide rallied in support of this woman’s concerns and hence drew a wider circle for tourism. The adorable Caretta Carettas that may reach 1,5 metres in length and 150 kilograms in weight are both the tourism industry’s symbol of the region and the of the Municipality of Dalyan. Their favourite food is the blue crabs of the Delta.

Iztuzu beach is one of the world’s best examples of people’s effort to preserve nature and to share it with other species. There are two ways to reach this natural wonder. Of course the best way is to get on one of the taxi boats from the Dalyan pier or rent a boat, and go on a wonderful journey. Your second option is the asphalt road starting at Dalyan town center and passing through the villages following the coast of the Sulungur Lake. This road gains elevation as you get closer to the beach giving you the opportunity to take wonderful photographs of the entire Delta reaching out to Iztuzu beach.

Iztuzu beach is one of the world’s best examples of people’s effort to preserve nature and to share it with other species. There are two ways to reach this natural wonder. Of course the best way is to get on one of the taxi boats from the Dalyan pier or rent a boat, and go on a wonderful journey. Your second option is the asphalt road starting at Dalyan town center and passing through the villages following the coast of the Sulungur Lake. This road gains elevation as you get closer to the beach giving you the opportunity to take wonderful photographs of the entire Delta reaching out to Iztuzu beach.

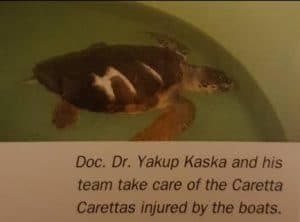

At the end of the road on the western edge of the beach there are two places that would attract the attention of any nature lover. The first of these is a small but meaningful museum that graphically displays the Caretta Caretta’s life cycle. The other is a research station (DEKAMER) where the sea turtles incurring debilitating wounds caused by entrapment in fishnets and hooks or moving boats are hospitalised In this centre scientists and students from Turkish universities as well as volunteers, work devotedly restore these wounded turtles treated in large saltwater tanks, which are then eventually reclosed back to nature.

Source: Koycegiz – Dalyan A Journey Through History Within The Labyrinth of Nature, (pages: 62-72), Altan Türe, 2011, Faya Kültürel Yayınları

Comments