Ovid’s Metamorphoses, translated to English by Anthony S. Kline

The sections he talks about the Byblis Legend – Creation of the Dalyan River

Bk IX:439-516 Byblis falls in love with her twin brother Caunus

Jupiter’s words swayed the gods: and no one could sustain their objection when they saw Rhadamanthos, Aeacus and Minos wearied with the years. When he was in his prime, Minos had made great nations tremble at his very name: now he was weak, and feared Miletus, who was proud of his strength and parentage, the son of Phoebus Apollo and the nymph Deione. Though Minos believed Miletus might plot an insurrection, he still did not dare to deny him his home. On your own initiative, Miletus, you left, cutting the waters of the Aegean in your swift ship, and built a city on the soil of Asia, that still carries its founder’s name.

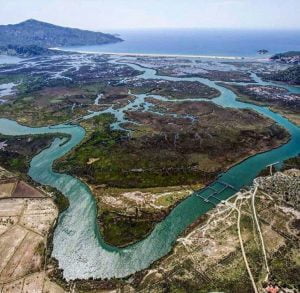

There you knew Cyanee, the daughter of Maeander, whose stream so often curves back on itself, when she was following her father’s winding shores. Twin children were born to her, of outstanding beauty of body, Byblis and her brother Caunus.

Byblis, seized by a passion, for her brother, scion of Apollo; that Byblis serves for a warning to girls, against illicit love. She loved, not as a sister loves a brother, nor as she should. At first, it is true, she did not understand the fires of passion, or think it wrong, to kiss, together, often, or throw her arms round her brother’s neck. For a long time she was deceived by the misleading likeness to sisterly affection. Gradually the nature of her love went astray, and she came looking for her brother carefully dressed, and over-anxious to look beautiful. If anyone seemed more beautiful to him, she was jealous. But her own feelings were not clear to her, and though she had no inner longing for passion, nevertheless it burned. And now she called him her lord, now she hated the name that made them related, now she wrongly wished him to call her Byblis, rather than sister. While she is awake she still dare not allow her mind its illicit hope, but, deep in peaceful dreams, she often sees what she loves, and is also seen, held in her brother’s arms, and she blushes, though lost in sleep.

When sleep has vanished, she lies there for a long time, recalling, to herself, the imagery of her dream, and at last utters these inner doubts: ‘Alas for me! What does it mean, this vision out of the night’s silence? How I would hate it to be true! Why do I see these things in sleep? He is truly handsome, even to unfriendly eyes, and is pleasing, and if he were not my brother I could love him, and he would be worthy of me. Being his sister is the reality that harms me. Let sleep often return with similar visions, as long as I am not tempted to do any such thing while awake! A dream lacks witnesses, but does not lack pleasure’s counterpart. By winged Cupid, and Venus, his tender mother, how great the joy I had! How clearly passion touched me! How my whole heart melted where I lay! What joy in remembrance! Though its pleasure was short-lived, and night rushed onwards, envious of my imaginings.

O if I could have been joined to you, with another’s name, Caunus, how good a daughter-in-law I could have been to your father! O Caunus, how good a son-in-law you could have been to my father! We would have had everything shared between us, except our grandparents: I would have wanted you to be nobler than me! You, most beautiful one, will make someone else the mother of your children, but to me, whom evil luck has given the same parents, you will be nothing but a brother. What separates us: that we will share as one. What does my vision signify to me? What weight indeed do dreams have? Or perhaps – the gods forbid – dreams do have weight? Certainly, the gods have possessed their sisters. So, Saturnled Ops, his blood-kin, to join with him, and Oceanus, Tethys, and the ruler of Olympus, Juno. The gods have their own laws! Why try to relate human affairs to other, divine, behaviour? Either my forbidden passion will be driven from my heart, or if I cannot achieve that, I pray to be loved, before I am laid out on my deathbed, and my brother kisses me there. Yet that needs both our wills! Suppose it pleases me: it may seem a sin to him.

Still, the sons of Aeolus, god of the winds, were not afraid to marry their sisters! Where did I learn that? Why do I have such ready examples? Where is this leading? Vanish, far off, illicit flames, and let my brother not be loved, except as a sister may love him! Yet, if he himself were first captured by love of me, I might perhaps be able to indulge this madness. Then let me woo him, whom I would not reject, if he were wooing! – Can you say it? Can you acknowledge it? – Love compels me: I can! Or if shame closes my lips, a secret letter will confess my hidden passions.’

Bk IX:517-594 The fatal letter

This idea pleases her, and this decision overcomes the doubt in her mind. Turning on one side and leaning on her left elbow, she says to herself: ‘Let him know: let me acknowledge my insane desires! Alas, where am I heading? What fire has my heart conceived?’ And, with a trembling hand, she begins to set down the words she has contemplated. She holds the pen in her right hand, and a blank wax tablet in her left. She begins, then hesitates; writes and condemns the writing; scribbles and smoothes it out; alters, blames and approves; in turn lays down what she has lifted, and lifts what she has laid down. She does not know what to do, displeased with whatever she is about to do. In her expression, shame is mixed with boldness.

She had written ‘sister’, but decided to efface the name of sister, and inscribed these words on the corrected tablet: ‘That wish, for long life, that she will not have, unless you grant it, one who loves you, sends to you. She is ashamed, oh, ashamed to tell her name. And if you ask what I desire, I would have wished to plead my cause, namelessly, and not to have been identified, until the expectation of what I desired was certain, as Byblis.

True, you might have seen signs of my wounded heart in my pallor, thinness, features, eyes full of tears, sighs with no apparent cause, frequent embraces, kisses, which, if you had chanced to notice, might not have felt like a sister’s. Yet, though my soul was deeply stricken, though the mad fire is in me, I have done everything I can (the gods are my witnesses) to become calmer. For a long time I have struggled, unhappily, to escape Cupid’s onslaught, and I have suffered more hardship than you would think a girl could suffer. I am compelled to confess, I have lost, and to beg your help, with humble prayers. You alone can save your lover, you alone destroy her. Choose what you will. It is not your enemy who prays to you, but one who, though closest to you, seeks to be closer still, and bound to you with a tighter bond.

Let old people know what is right, and what is allowed, and what is virtue and what is sin, and preserve the fine balance of the law. At our age Love is what is fitting, that takes no heed. We do not know yet what is permitted, and we consider all things permitted, and follow the example of the great gods. We have no harsh father, no regard for reputation, and no fear to impede us. Even if there were cause for fear, we can hide sweet theft under the names of brother and sister. I am free to speak to you in private, and we can embrace and kiss in front of others. How important is what is still lacking? Pity the one who confesses her love, and would not confess if extreme desire did not force her, and do not you be the reason for the writing on my tomb.’

Her handwriting filled the wax, with these fruitless words, the last line close to the edge. Immediately she put her seal on the sinful message, dampening it with her tears (moisture failed her tongue), stamping it with her signet ring. Shamefacedly, she called one of her servants, and shyly and coaxingly said: ‘You are most faithful. Take these to my……….brother’ she added after a long silence. As she let them go, the tablets slipped and fell from her hand. She still sent the letter, troubled by the omen. Finding a suitable time, the messenger went, and delivered the hidden words. Horrified, Maeander’s grandson, suddenly enraged, hurled away the tablets, he had accepted, and partly read, and, scarcely able to keep his hands from the trembling servant’s throat, cried: ‘Run while you can, you rascally aide to forbidden lust! I would deal you death, as a punishment, if your fate would not also drag our honour down with it.’ The servant fled in fear, and reported Caunus’s fierce words, to Byblis.

She grew pale, hearing that she had been rejected, and her body shook, gripped by an icy chill. But, when consciousness returned, so did the passion, and, she let out these words, her lips scarcely moving: ‘I deserve it! Well, why did I rashly reveal my wound? Why was I in such a hurry to commit things, which were secret, to a hasty letter? I should have tested his mind’s judgment before by ambiguous words. I should have observed how the winds blew; used other lesser sails, in case those breezes were not to be followed; and crossed the sea in safety, not as now, under full canvas, caught by uncertain gusts. So I am carried onto the rocks, swamped, overwhelmed by the whole ocean, and my sails have no means of retreat.’

Bk IX:595-665 The transformation of Byblis

‘Why, as far as that is concerned, everything, unerringly, warned me not to give way to my desire, at the moment when the tablets fell, as I was giving orders for them to be taken to him, meaning that my hopes would also fall away. Should not, perhaps, the day, or my whole intention, more so the day, have been altered? The god himself issued a warning, and gave a clear sign, if I had not been crazed with love. Also I should have told him myself, and revealed my passion to him in person, and not committed myself in writing. He would have seen the tears, and seen a lover’s face. I could have said more than any letter can contain. I could have thrown my arms around his unwilling neck, and if I had been rejected, I could have seemed on the point of dying, embraced his feet, and lying there begged for life. I should have done all those things that, if not singly, all together, might have persuaded his stubborn mind. Maybe the messenger who was sent was at fault: did not approach him properly, I think, or choose a suitable moment, or discover when he and the time were free.

It has all harmed me. Truly, my brother is not born of the tigress. He does not have a heart of unyielding flint, solid iron, or steel. He was not suckled on the milk of a lioness. He will be won! I will try again, and not suffer any weariness in my attempts, while breath is left to me. Since I cannot undo my actions, it would have been best not to begin: but, having begun, the next best is to win through. In fact if I relinquished my longing, he could still not fail to remember what I have dared, and by desisting I will be seen to have been shallow in my desires, or to have been trying to tempt and snare him. He will even believe, I am sure, that I have not been conquered by the god, who, above all, impels and inflames our hearts, but by lust. In short, I cannot but be guilty of impiety, of writing, of wooing: my wishes are revealed. Though I add nothing to them, I cannot be said to be innocent. There is little left to be accused of, but much to long for.’

So she argues, and (so great is the undecided conflict in her mind) while she repented of the attempt, she delights in attempting. Going beyond all moderation, and unsuccessful in what she tries, she is endlessly rejected. Finally, when there seems no end to it, he flees from this wickedness and from his home, and founds a new city in a foreign place: Caunus, in Caria.

Then, indeed, grief made Miletus’s daughter lose her mind completely. Then, indeed, she tore the clothes from her breast, and beat her arms in frenzy. Her madness was now public, and she confessed her hope of illicit union, by leaving the country she hated, and her household gods, and following the footsteps of her fleeing brother. The women of Bubasos saw Byblis, howling in the open fields, as your Thracians, son of Semele, pricked by your thyrsus, keep your triennial festival.

Leaving them behind she wandered through Caria, through the lands of the armed Leleges, and on through Lycia. Now she was beyond Lycian Cragus, and Limyre, and the waters of the Xanthian plain, and the ridge of Mount Chimaera near Phaleris, where the fire-breathing monster lived, joining a lion’s head and chest to a serpent’s tail. Above the woods, when, wearied, you were weak from following, you fell, Byblis, your hair spread on the hard earth, and your face pressing the fallen leaves.

The Lelegeian nymphs often try to lift her in their tender arms, and often they teach her how she might remedy her love, and they offer comfort to her silent heart. She lies there, mute, clutching at the green stems with her fingers, and watering the grass with her flowing tears. They say the naiads created a spring from them, beneath her, which could never run dry. Well, what more could they offer her? There and then, Byblis, Phoebus’s granddaughter, consumed by her own tears, is changed into a fountain: just as drops of resin ooze from a cut pine, or sticky bitumen from heavy soil, or as water, that has been frozen by the cold, melts in the sun, at the coming of the west wind’s gentle breath: and even now in those valleys it retains its mistress’s name, and flows from underneath a dark holm oak.

You can access and download the full script from below link:

Ovid’s Metamorphoses, tr. Anthony S. Kline

Comments