Research shows that the sea turtles living in the Mediterranean are species that are partly genetically modified. The meaning of this is that, apart from accidental entries and exits, Mediterranean sea turtles do not go to the ocean after laying eggs. Turtles of other seas, also, do not enter the Mediterranean. However, Mediterranean sea turtles can migrate between their reproduction and wintering areas within this sea. The Greek, Turkish and Cyprus coasts are their most important nesting areas while the shores of Tunisia, Libya, Italy and Spain are their most important wintering and feeding areas. More than half of the Mediterranean Caretta Caretta pulation come to Turkey’s Western and Central Mediterranean coasts, especially to Iztuzu, Belek, Kizılot and Anamur, to lay eggs. It is known that yearly an average of 2000 Caretta Caretta nests are made in the Turkish coast and that an average of 100 eggs is laid in each nest. Considering that a mature female makes a nest 4 to 8 times each season, we know that annually about 500 Caretta Caretta females nest in the beaches of our country. Only a scant few, about 2 or 3 of the 1000 young that are able to hatch, live for 25 years and reach maturity.

Factors such as industrialisation, which has developed parallel to the rapidly increasing human population in the last 50 years, tourism and shore fishing, threaten the balance of nature. While the Mediterranean, which is a closed basin, becomes increasingly polluted, beaches that are the turtles’ natural nesting habitat have lost their natural characteristics. Not able to avoid the boats, the number and speed of which have rapidly increased, the turtles hit the propellers and receive severe wounds. In their effort to free themselves from the fishing lines to which they get caught the lines cut their flesh and open deep cuts in their legs. As they are able to remain underwater for two hours at the most, they drown when they get caught in fishing nets. The number of premature deaths increases due to these and similar reasons.

Another great danger threatening them is transparent plastic bags. The turtles mistake these bags, which are dragged into the sea by rivers or which are carelessly thrown into the sea from boats, for their favourite food, jellyfish; but the plastic blocks their digestive tract and causes them to die. The sea turtles, which were able to fend off extinction for 160 million years adapting to the varying conditions of the glacial and arid epochs, is one of the oldest living species on earth, their continuation as a species, however, is now altogether dependent on man’s sensitivity. All of the sea turtle species living throughout the world have been designated as “endangered” by the International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources (IUCN). Turkey is also among the countries that undertake to protect the sea turtles and their habitats.

The arrangement of the Iztuzu Beach so as to ensure the cohabitation of human beings and nature is a successful example of adherence to this undertaking and respect towards mother nature. The Sea Turtles Research, Rescue and Rehabilitation Centre (DEKAMER), known as The Turtle Hospital, was established on 7th October 2009. The centre continues its training activities to promote “public awareness towards preservation which is one of its missions.

“Kaptan June Sea Turtle Conservation Foundation,” established in 2011 by June Haimoff and her friends, has been very effective in helping the conservation of the sea turtles, Dalyan Iztuzu Beach and the Koycegiz-Dalyan Natural Reserve.

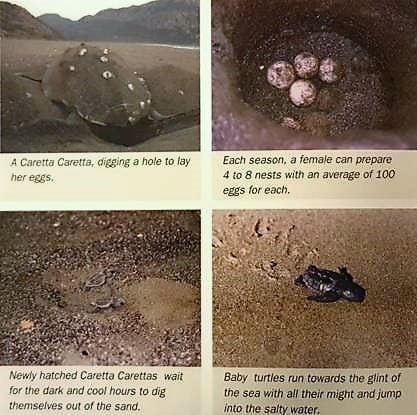

In the Caretta Carettas’ life cycle, each maturing generation returned to the beach it was born for reproduction. They mated in the shallow water of the beach they recognise, thanks to a million-year genetic memory and buried their eggs into the nests they opened in the sand of the same beach. The Caretta Carettas reach sexual maturity at 25 and reproduce in March, April and May. Their egg-laying season is the months of June, July and August. In order to lay the eggs fertilised with the sperms they store and keep alive, the females bury about 90-100 eggs into the holes they open in the beach at a frequency of 4 to 8 times a night at 12-13 day intervals.

Reproduction is a difficult and sustained duty nature has assigned to female turtles. Their heavy bodies that glide like a bird in the deep blue and their flipper-like feet are not at all suitable for walking on land, but dragging themselves on the sand, leaving trails like tank tracks, look for the most suitable place for a nest. Some nests are only empty holes dug and closed in order to confuse foxes, jackals and dogs that follow turtle trails to plunder the nests.

Incubation lasts two months, and if the temperature of the sand is above 37° centigrade during this period, all of the young in the nest become females and cooler temperatures produce male offspring. The eggs hatch while the parching heat of the sun burns the sand, but the young, upon instinct, wait for the dark and cool hours of night to dig the sand and tread on each other to get out. Then they run towards the pale glint of the sea with all their might and jump into the salty water. Nature has equipped them with two special devices in their competition on the thin line that separates life and death. The Loggerheads with two features that help them in their race to defy death. The tusk-like projection on the heads of the young turtles enables them to crack the shell of the egg and then disappears in time. A pea-size accumulation of fat in their abdomen is the energy stock they require to reach the sea quickly.

This race to live and die is full of obstacles, most of which are man-made. If there are bright lights on the beach due to camps and facilities, the young go inland towards them instead of the sea. When they fall into the deep tracks of car wheels and holes they are mostly unable to get out and fall prey to seagulls, crabs and other carnivores when the sun rises or dehydrate and die. Reaching the sea does not guarantee life for these cute little turtles They have to swim 24 hours non-stop to reach open seas in order to avoid the large predatory fish that wait for them in the coastal waters.

Saklıkent & Gizlikent Adventure Tour

Private Dalyan Boat Trip

Noon to Moon Boat Trip

Source: Koycegiz – Dalyan A Journey Through History Within The Labyrinth of Nature, (pages: 101-105), Altan Türe, 2011, Faya Kültürel Yayınları

Comments