“Being a city-dweller is not ignoring the historyof the city you live in, it is to take root.”Mustafa Pala

While giving important information of Caria’s history and Caria’s cities during the Persian Wars, Herodotus, whose father was a Carian from one of the prominent families of Halicarnassus, and whose mother was a Cretan, speaks of Caunos saying: “Harpagos (Persian general), who brought Ionia to heel, marched against the Carians, Caunosians and Lycians.” This passage relates to the Persian invasion of Western Anatolia in 546 BC, with Caunos and its adjoining cities highlighting it as an independent region with a different language and different customs. In Chapter 1.72 of his History, Herodotus elucidates : “I believe that the inhabitants of Caunos are natives of the region. But they say that they came from Crete. Carian influence is traceable in their language, or vice versa…” This is a point I have not been able to further clarify. The fact that letters not found in the Carian alphabet were seen in tablets inscribed in the local language which were excavated during digs in Caunos, appears to confirm the theory of a separate language or a distinct dialect of the same.

Also, the customs and beliefs of the people of Caunos are very different from those of Carians and Lycians. On this point, Herodotus says: “But their customs are different from those of Carians and Lycians. One of these much revered customs is that friends or those of the same age come together, whether men women or children, and drink wine.” Agreeing with the Carian Federation’s resolution to make war during the Persian invasion, Caunos, together with Mindos and the small Leleg city called Pedesa on the same peninsula, weakened the Persian army after a long and stubborn resistance. By relating to us that “the Xanthians of Lycia, although outnumbered, retreated to their city after fighting the Persians bravely, gathered their wives, children and property within the citadel and set fire to it, then attacked the enemy and died with their swords in their hands,” Herodotus praises the Caunosians who defended their city to the death.

Herodotus also relates some interesting information concerning their attachment to their beliefs: “At some other time these people gathered and decided to worship only in the temples of their forefathers rather than using the foreign temples built in their city. After some time, all of the young men of the city were armed, went up to the Calyndan border waiving their spears and said that they had banished the foreign gods.” So, what were the names of their ancestors’ gods and which powers did they represent?

According to the people of Caunos, their ancestors had emigrated from Crete, according to Herodotus’ interpretation they may be natives of this land. In both cases, however, the most ancient deity they worshipped was the mother goddess, the origins of which go back to the Palacolithic Era. The monolith shown sometimes as a crudely hewn menhirand and sometimes as a schematized steep pyramid on the coins of Caunos, is the most widely spread cult object of the mother goddess. She reigned over birth and death, the balance of nature and the cycle of seasons as seen in the Cybele cults of other regions.

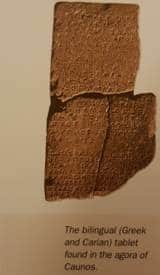

During the 5-4th centuries BC, when the Hellenic culture started to influence Anatolia, the cit started to use the Greek name Caunos as well as its native name Kybid. This new name also gave the city a Hellenic identity by introducing a myth of a legendary king. According to this mytlh Caunos, son of Milatos, fleeing from the passionate love his sister Byblis had for him, founded the city Caunos after his own name. On a stele found in the Xanthos agora, written in three languages (Lycian, Greek and Aramaic) and dating back to the 4th century BC, it mentions that a shrine was built for the Caunosian king who was given a fertile land. This would indicate that Caunos legendary founder was revered in neighbouring cities as well. However, the Lycian part of this tablet uses the name “Kbid” while the Greek part uses “Caunos.” The bilingual (Carian and Greek) tablet found in the agora of Caunos in 1996 and dated back to the 4th century BC also confirms this assumption. In the Greek version of the same text the city is mentioned as Caunos while the Carian text mentions the city as Kbid. This archaeological evidence proves that the name Kbid was used until the end of the 4th century BC (Öğün Işık-2001)

During the 5-4th centuries BC, when the Hellenic culture started to influence Anatolia, the cit started to use the Greek name Caunos as well as its native name Kybid. This new name also gave the city a Hellenic identity by introducing a myth of a legendary king. According to this mytlh Caunos, son of Milatos, fleeing from the passionate love his sister Byblis had for him, founded the city Caunos after his own name. On a stele found in the Xanthos agora, written in three languages (Lycian, Greek and Aramaic) and dating back to the 4th century BC, it mentions that a shrine was built for the Caunosian king who was given a fertile land. This would indicate that Caunos legendary founder was revered in neighbouring cities as well. However, the Lycian part of this tablet uses the name “Kbid” while the Greek part uses “Caunos.” The bilingual (Carian and Greek) tablet found in the agora of Caunos in 1996 and dated back to the 4th century BC also confirms this assumption. In the Greek version of the same text the city is mentioned as Caunos while the Carian text mentions the city as Kbid. This archaeological evidence proves that the name Kbid was used until the end of the 4th century BC (Öğün Işık-2001)

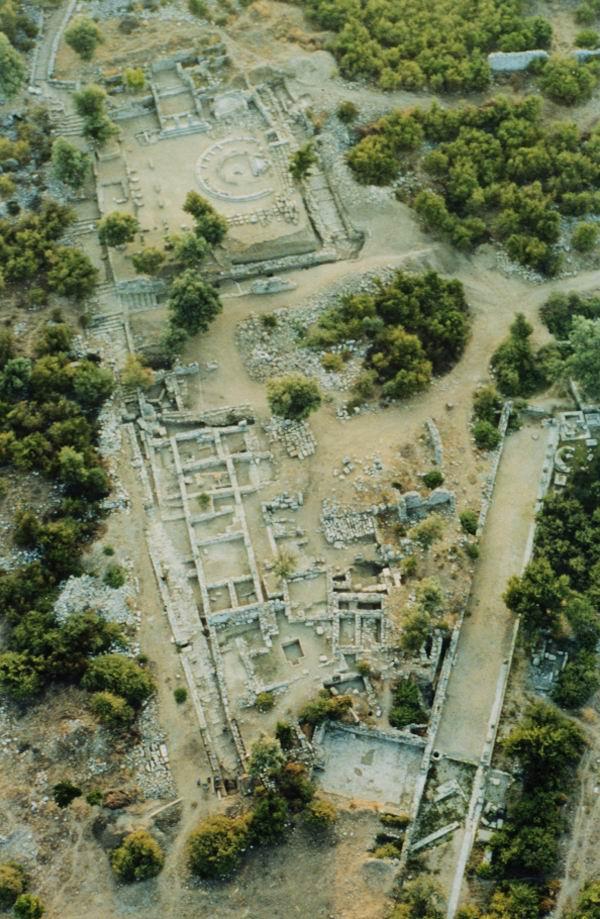

The era, after Caunos was annexed to the Caria satrapy of the Persian Empire under the rule of the Hekatomnus dynasty, especially during the period of Mausolus (377-353 BC), saw great changes. The city was enlarged and developed on a terraced plan used in Persian cities and was surrounded by walls covering a vast area. Although it was not a Greek colony, it progressively turned into one, with its agora and its temples dedicated to Greek gods. while ancient Greek became prominent as the spoken and written language, the Carian name in the inscriptions left their places to Greek names.

Among all this change, the menhir of Cybele turned into the symbol of the god-king Basileus Caunos, the founder and patron of the city. This slightly shaped monolith of 3.5 metres became the centre of the religious world of Caunos from the 5th century BC to the advent of Christianity, and a symbolic cenotaph (Hereon) was erected over it in the 1st century AD.

Like Artemis of Ephesus and Aphrodite of Aphrodisias, the mother goddess of Anatolia fused with the Mesopotamian goddess Ishtar and the nature goddesses of Greek mythology to form local goddesses. The Caunos Artemis that was found during the excavations conducted in the Apollon Temanos area and is now exhibited at the Fethiye Museum, is a good example of the new and local mother goddess cults born of the synthesis of the eastern and western cultures during the Hellenistic Era. Carved out from a rectangular block, animal figures ornament the frontal portion of the body, depicting a goddess not unlike the Ephesian Artemis.

The goddess of love and war named Ishtar, Astarte and Ashtoreth was worshipped in the ancient cults of Mesopotamia.This powerful goddess was represented by the planet Venus, which is conspicuous for being the brightest object in the night sky after the moon. The goddess called Aphrodite by the Greeks and Venus by the Romans, was borrowed from classical mythology by eastern cults, but was accepted only as a goddess of love. Greek myth relates that Aphrodite was born of foam at the Cypriot shore. Therefore, Aphrodite, who represents “beauty” coming from the sea as well as being a star goddess conferring her blessings to sailors, had a valued role in Caunos. Seamen would come to the altar at the Aphrodite Euploia sanctuary adjoining the rear side of the agora stoa to express their gratitude for a safe and profitable journey while those who were about to depart would make offerings for good luck.

According to what is told by some travellers of the antique world, Stratonikos, the lamous musician (harpist) and wit who lived in the 4th century BC, lived for a while in Caunos. Upon seeing the pale faces of the locals suffering from malaria, he was said to have quoted Homer “a man’s life is like that of leaves.” When people complained that he cruelly tarnished the city by branding it as “sickly,” Stratonikos said “What! Am I so arrogant to call the city sickly when so many dead are wandering about?’’

Indeed, malaria, which turns people into the living dead with their yellowish complexion and swollen bellies, gave Caunos a bad reputation. Speaking of Caunos; Strabo says, “although its land is fertile, it has an unhealthy air due to heat and an abundance of fruit even in autumn as everyone agrees.” In the days of old when people did not know that the malaria virus was caused by the anopheles mosquito, they thought the diocese spread through the polluted air rising from swamps. However, the connection Strabo draws between malaria and fruits is related to the opinion of Galen, the famous physician of antiquity, when he said “malaria is connected with fruits. My father died when he was 100 because he stayed away from fruit.” The most famous among Caunos’ abundant fruits mentioned by Strabo were figs. Today there are not many fig trees around Dalyan, but fresh and dried figs were a favourite dish with the ancients and were among Caunos’ most important exports.

Indeed, malaria, which turns people into the living dead with their yellowish complexion and swollen bellies, gave Caunos a bad reputation. Speaking of Caunos; Strabo says, “although its land is fertile, it has an unhealthy air due to heat and an abundance of fruit even in autumn as everyone agrees.” In the days of old when people did not know that the malaria virus was caused by the anopheles mosquito, they thought the diocese spread through the polluted air rising from swamps. However, the connection Strabo draws between malaria and fruits is related to the opinion of Galen, the famous physician of antiquity, when he said “malaria is connected with fruits. My father died when he was 100 because he stayed away from fruit.” The most famous among Caunos’ abundant fruits mentioned by Strabo were figs. Today there are not many fig trees around Dalyan, but fresh and dried figs were a favourite dish with the ancients and were among Caunos’ most important exports.

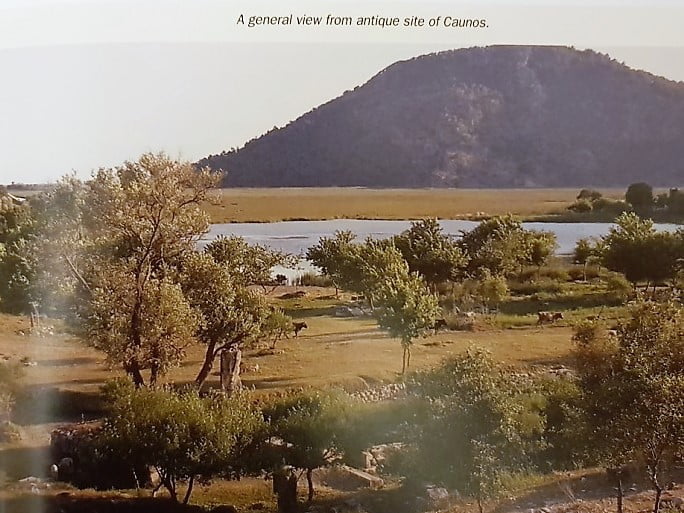

Providing valuable information on Caunos’ city plan and natural environment of the 1st century Strabo relates that “Caunos has shipyards and a harbour that can be closed, and that there is a castle further up the city called Imbroz by the Calbis River courses and is navigable by ships flows,”

The Calbis River is the Dalyan River that leaves the Köycegiz Lake and flows into the sea. The rock on which the small acropolis stood in antiquity was probably a peninsula with harbours at two sides. The place which Strabo describes as a closed harbour is the Sülüklü Lake in front of which stands the agora stoat today; (the word “closed” most probably refers to the chain strung across the entrance of the cove for protection). The location of the shipyard where ships were built, repaired and maintained has not yet been identified. The castle of Imbroz is the large fortress that encloses the peak of the Ölemez Mountain.

The people of Caunos had been punished many times during the political and military conflicts of the Hellenistic Era, the Roman Republic and early Empire periods for supporting the side that was defeated. The worst of these punishments was being subjected to control by Rhodes, which they hated. In a satire dated to 70 BC, the sophist Dio Chrysostomos criticised the people of Caunos who had to suffer the double rule of Rhodes and Rome, saying: he stupid people of Caunos… Was there ever a famous person from that city? Who treated them well? They have no one to blame but themselves for this bad fortune of theirs. If it is not really malaria that caused this condition, what they have suffered is too little compared to what they deserve.”

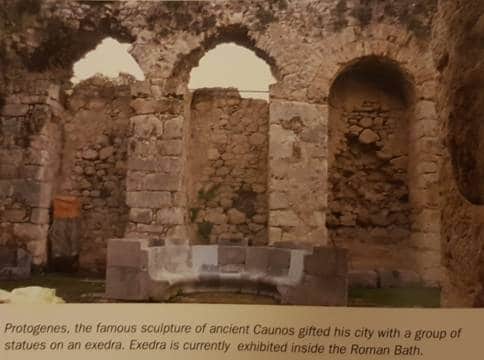

These harsh words were in a sense wrong. Yes, Caunos which was a trade port saw a hardy race of men living on the steep terrain of Caria; it had not raised any thinkers that would elicit political support nor poets or writers to bring honour to its city. But the people of Caunos could be proud to have a fellow townsman such as Protogenes, one of the most important fresco painters and sculptors in the Era of Alexander the Great.

These harsh words were in a sense wrong. Yes, Caunos which was a trade port saw a hardy race of men living on the steep terrain of Caria; it had not raised any thinkers that would elicit political support nor poets or writers to bring honour to its city. But the people of Caunos could be proud to have a fellow townsman such as Protogenes, one of the most important fresco painters and sculptors in the Era of Alexander the Great.

The city that was forgotten after being abandoned in the 15th century, was briefly remembered when Honsken the traveller read the name “Caunos” on a tablet in the ruins, but it attracted the attention of only two researchers between 1877 and 1920. The Turkish government’s arduous efforts in the 1940s to completely exterminate malaria and which was successful, made Caunos a better place for visitors. When George E. Bean published the research he conducted in the ruins of Caunos between 1946 and 1952, and when the American journalist Freya Stark, stopped by at Caunos on her trip to the Aegean and the Mediterranean on board the yacht “Dolphin” and wrote about the city in her travel book entitled, “The Lycian Shore”, this enchanting city was once more brought to public attention. With the excavations initiated by Prof. Dr. Baki Ögün in 1966 on behalf of Ankara University and continued by Prof. Dr. Cengiz Işık, the city of Caunos/Kbid has once more seen the light of day.

Source: Koycegiz – Dalyan A Journey Through History Within The Labyrinth of Nature, (pages: 116-124), Altan Türe, 2011, Faya Kültürel Yayınları

Comments