“Now green in youth, now withering on the groundAnother race the following spring suppliesThey fall successive, and successive rise”Homer

The most ancient find of the Caunos excavations is a piece of a protogeomeric amphora dating back to the 9th century BC. In addition to this, the geometrical style designs of ceramic vessels patterned with concentric circles drawn between lateral bands or with semicircular motifs, were products of local pottery workshops and Herodotus’ comment that the people of Caunos were the natives of the land, brings to mind a settlement that dates far back. However, no architectural objects that can be dated to before the 4th century BC have been found in Caunos as yet. A statue of a young man that was  excavated in front of the western gate of the city walls, pieces of Attic ceramic with black-figure patterns, which were expensive imported objects, as well as the archaic walls that surround the city in a south to south-easterly direction, woven with large boulders, some of which were roughly hewn to sit on each other, are archaeological proofs of the 6th century BC.

excavated in front of the western gate of the city walls, pieces of Attic ceramic with black-figure patterns, which were expensive imported objects, as well as the archaic walls that surround the city in a south to south-easterly direction, woven with large boulders, some of which were roughly hewn to sit on each other, are archaeological proofs of the 6th century BC.

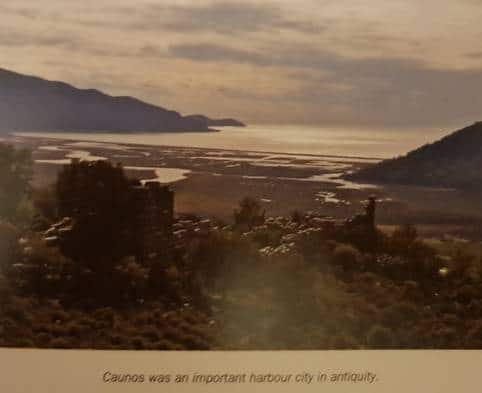

These finds indicate that Caunos had been a rich and important seaport after the 6th century BC. However, Caunos is not mentioned in historical sources until the Persians destroy the kingdom of Lydia in 546 BC and annexed the whole of Anatolia.

The earliest and most important information on Caunos is given by Herodotus, who relates that “the people of Caunos put up a fierce resistance against the Persian general Harpagos, but were eventually defeated.” In the years following Xerxes’ defeat in his Greek campaign and the Persians’ having to retreat from the coast of Western Anatolia, Caunos, like many other seaports, took part in the Dalian League, formed by the Athenians against the Persians. At the beginning Caunos paid the League only a nominal tax, as little as half a talent. However, in 425 BC this tax was suddenly raised to the same amount paid by Miletos, which was 10 talents (silver coins equal to 3 thousand Republic gold coins). There is no proof that this high amount was actually paid, but what is interesting is that it indicates that the city suddenly became richer. The source for this sudden wealth may be because the people of Caunos opened new farmland, or because the demand for the city’s exports, which were salt, salted fish, slaves, pine resin, and the pitch that was obtained by burning this resin.

The fact that Thucydides, who recounts the Peloponnesian Wars between the Athenians and the Spartans resulting in Athens defeat, mentions that “the fleets of both sides used the port Caunos” which indicates that Caunos pursued a flexible policy. The King’s Peace of 387 BC placed Caunos back under Persian sovereignty like all other coastal cities of Anatolia. During the Hekotomnos dynasty that ruled the Carian satrapy of the empire especially during the reign of Mausolus, the city was enlarged with a new building plan involving terraces on the steep land, and was enveloped with walls. The Asian campaign that started when Alexander the Great, king of Macedonia, set foot on Anatolian soil in 334 BC resulted in the destruction of the Persian Empire and the rise of the Hellenistic Empire. However, there was continuous conflict between the emerging Hellenistic kingdoms shared by Alexander’s generals upon his death in 323. Being a strategic seaport, Caunos kept changing hands, resulting from invasions and political manoeuvres, and became a Rhodian dominion a couple of times.

The balance of power began to shift when Rome, rising as a new imperialistic force in world history, started annexing all Hellenistic kingdoms through war or politics. When Antiochus, King of Syria as defeated in the war he waged with Rome in Magnesia in 189 BC, the Roman Senate left the administration of all of Cari Lycia to Rhodes. Having had enough of Rhodian oppression, the western Anatolian cities rose in revolt in 167 BC. This revolt, in which Caunos also took part, was suppressed, but Romans mad Rhodes leave the Anatolian soil.

In 129 BC, Rome founded the “Province of Asia’ that covered a large part of western Anatolia. Being one of the border cities of this province Caunos was attached to Lycia after a revised administration plan Under Roman rule, citizens of Rome, most of whom were traders and bureaucrats, started to live in Anatolian cities. Combating Roman expansion, Mithridates, King of Pontus, invaded the region in 88 BC The people of Caunos supported the king and brutally killed all Romans in their city.

After making peace in 85 BC, Rome dealt Caunos a severe punishment and once more put them under the rule of those despised Rhodians. Towards the ends of the 1st century BC, Caunos once more gained its independence. However, the fact that the Sophist Dio Chrysostomos mentioned that “the people of Caunos had to suffer the double rule of Rome and Rhodes” and in his writing dating back to 70 AD, indicates that the Rhodians once again had a say in the city’s affairs.

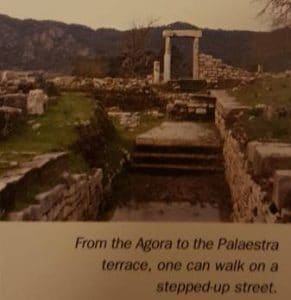

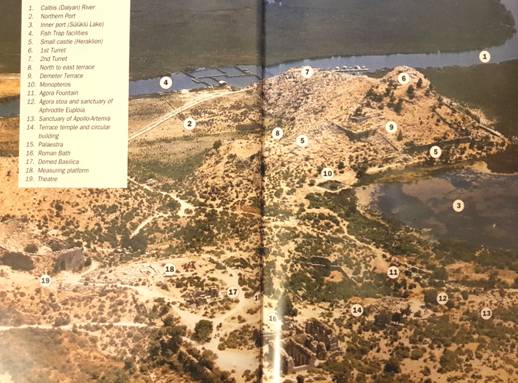

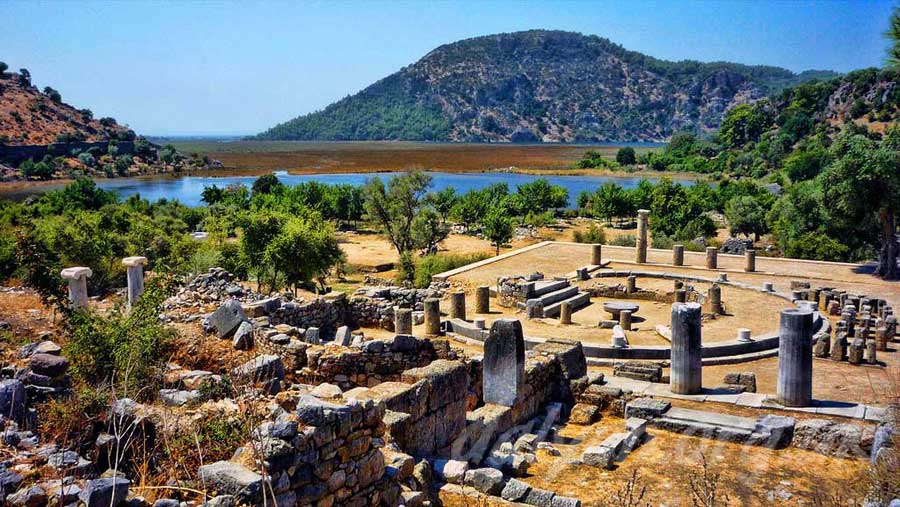

For the centuries that Rome thrived peacefully as an empire, Caunos was free of military and economic pressure and continued its existence as a rich seaport. In the early years of the Empire, the theatre underwent an enlargement almost at the scale of a full restructuring, at which time a large bath essential for a Roman city) and a wide palaestra were built on the terrace just in front of it. The Agora fountain was also renewed and temples were built. The people of Caunos erected statues of the Roman emperors Tiberius, Nero and Vespasian as well as those of Roman ambassadors and senators around the agora and on the Apollo sanctuary in order to demonstrate their loyalty. They even honoured famous Romans who visited their city by erecting their statues.

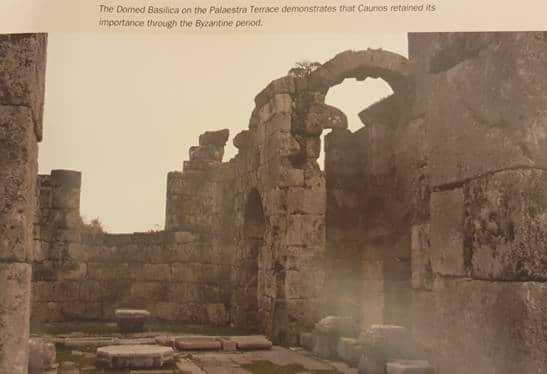

The rock on which stands Caunos’ small castle and the cove to the north of the peninsula had already become a swamp that filled gradually and was abandoned by the 8th century. The inner port of the cove to the south of the island was still open to the sea, however. But when the front of the southern port also became blocked with reeds and swampy waters between 100 BC and 200 CE, the city was cut off and left far from the sea. When in the tumultuous time that the Roman Empire officially adopted Christianity as its religion, and any trace of paganism was destroyed especially temples to gods and goddesses, Caunos must have been considered a prominent centre, with its five churches standing proudly atop the hill.  During this period Caunos’ name was christianised to become Caunos-Hegia, as it was zoned within the Episcopal Lycia province and subjected to the two Papal Sees With all turmoil of Muslim-Arab raids and pirate attacks after 625, and then the Turkish invasion at the beginning of the 13th century, the ancient castle at the top of the Acropolis was fortified with Byzantine walls. These walls, a greater part of which still stand, lent Caunos the appearance of a medieval city. Caunos was completely abandoned after Turkish tribes overran the whole of Caria in the 15th century (Öğün, Işık 2001).

During this period Caunos’ name was christianised to become Caunos-Hegia, as it was zoned within the Episcopal Lycia province and subjected to the two Papal Sees With all turmoil of Muslim-Arab raids and pirate attacks after 625, and then the Turkish invasion at the beginning of the 13th century, the ancient castle at the top of the Acropolis was fortified with Byzantine walls. These walls, a greater part of which still stand, lent Caunos the appearance of a medieval city. Caunos was completely abandoned after Turkish tribes overran the whole of Caria in the 15th century (Öğün, Işık 2001).

Source: Koycegiz – Dalyan A Journey Through History Within The Labyrinth of Nature, (pages: 126-133), Altan Türe, 2011, Faya Kültürel Yayınları

Comments